Books of the Year 2019 / Part Four

Contributors to The Lonely Crowd pick the best books that they have read this year.

Jaki McCarrick

My reading in 2019 was disparate and strange. At night I mostly read fiction, some novels I had already read or missed classics or works published a few years previously. During the day, I read books I’d been asked to review, much of these scholarly works and some poetry. Obsessed with the political situation in the UK, I also read what I could about this, mostly in newspapers and online. I also spent time researching the subject of the Irish Diaspora in the UK for a lecture I gave in London in November. So this year my reading was often pulled, uncomfortably, in several directions at once, with much of my best reading time given over to reviews and research.

My favourite contemporary novel of the year was undoubtedly Marlon James’ Black Leopard, Red Wolf. This is a dark fantasy tale, set in a mythical world, and part one of a trilogy, Dark Star, about Tracker (who is said to “have a nose”) and his difficult redemption. As with James’ 2015 Man Booker Prize-winning A Brief History of Seven Killings, it’s a merciless and beautifully-written work, full of wonderful sentences such as “The sky was gray and fat with waiting rain” and “She came out of the trees as if out of the trees she sprung”. Neil Gaiman said of James’ latest novel, “it’s the kind of novel I never realised I was missing.” At 620 pages, it’s a big book, but also one of the bravest and boldest pieces of contemporary fiction I’ve read in years and is without a single lapse in energy or nerve.

I also enjoyed my re-reading of John Healy’s The Grass Arena, which I first read several years ago and returned to for my research into the Irish Diaspora in the UK. First published in 1988, The Grass Arena is the autobiographical story of a young London-Irish boxer who descends into a life of alcoholism and rough-sleeping on the streets of London, to then later find salvation through his skill in the game of chess. Some critical studies of the Irish Diaspora in the UK note the lack of London-Irish prose, as compared to, say, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth or Hanif Kureshi’s Buddha of Suburbia, though this beautiful book (which is more memoir than novel) is, I consider, on par with those much lauded works. The voice is clear and direct and, occasionally, like Marlon James’, thoroughly brutal. Healy’s book is also a fascinating tour of late-80s London, before widespread gentrification, when squatting (now illegal) provided a housing option for the homeless.

My favourite non-fiction books of 2019 were Gary Browning’s Why Iris Murdoch Matters.This is a compact scholarly work, which goes some way to explain the mechanics of Murdoch’s ability to bewitch readers – due of course to her dazzling literary style but also, as Browning confirms, to her moral philosophy, which is rooted in Plato and the European philosophers she came to admire while at Oxford and Cambridge, namely Sartre and Simone Weil. Overall, it’s a fascinating account of the philosophical underpinnings of the novels of one the greatest writers of the 20th Century. Murdoch also happens to be one of my favourite novelists, so I found Browning’s work particularly illuminating.

I also very much liked Faith Binckes’ and Kathryn Laing’s critical study of Hannah Lynch, Hannah Lynch (1859-1904): Irish Writer, Cosmopolitan, New Woman . It’s a brilliant account of an important Irish writer of the pre-Irish Independence period, who has, unfortunately, been largely written out of history. I also very much enjoyed Zadie Smith’s collection of essays, Feel Free, published in 2018.

My favourite poetry collections in 2019 were debuts – by Jo Burns and Rachel Coventry. Jo Burns’ White Horses is packed with great poems and contains a number of political pieces, which I enjoyed immensely. Her poem ‘Heart or Reason’ charts contemporary life in Germany, where Burns has lived for a number of years. In an obvious reference to Brexit and the current wave of nationalism in the UK, its speaker insightfully declares: ‘It’s our duty to warn how nations are duped when uncertain. / We have been there but now it’s looking red, white and blue.’ The Galway-based Coventry, meanwhile, explores in her collection Afternoon Drinking in The Jolly Butchers a background in London and Scotland. A number of poems in Section One of this collection also explore drug use, such as ‘The Lost’, in which the speaker watches a friend shoot up: ‘I said nothing in protest though / I could not watch the needle go in …’, and ‘Poppies’, in which a long-ago holiday in France is remembered, possibly with the same friend (as referred to in ‘The Lost’):

We fed on waxy balls of

Opium. I cannot say how long we stayed but one night the moon

was more full and more beautiful than it has ever been since.

2019 has been a heady and politically toxic year: a new rightwing Tory Government, widespread climate disaster, a widening gap between rich and poor, the spread of far right nationalism throughout the world. While this has undoubtedly been difficult for artists and writers to keep up with, in terms of mining the times for meaning (some artists of course don’t attempt to do this at all, which is their prerogative) – the year has nonetheless evidently entered the artistic bloodstream. Much of the writing I read in 2019 was angry and articulate and brave; those who would continue to damage the hard-won liberties and protections of the modern age will find that they have a fight – and many literary fighters – on their hands.

Jaki McCarrick is the author of THE SCATTERING, BELFAST GIRLS and THE NATURALISTS.

Arnold Thomas Fanning

Minor Monuments by Ian Maleney.

In a series of thematically connected essays, deftly executed, Ian Maleney writes on place, nature, art, the past, and his relationship with an older generation in his family history, deftly moving from the intensely personal to wider considerations of the writer’s place in the world. It’s also, appealingly, a book about the writing of a book; a complex and considered meditation.

The Scar: A Personal History of Depression and Recovery by Mary Cregan.

Mary Cregan writes powerfully of her harrowing experiences of mental distress and hospitalisation, of loss and grief, and of the long but ultimately redemptive journey to recovery, all the while placing her own personal story in the larger context of a cultural and historical study of psychiatry and mental illness. A compelling, moving, and memorable account.

Constellations: Reflections from Life by Sinéad Gleeson.

Winner of the An Post Irish Book Awards Bookselling Ireland Non-Fiction Book Of The Year 2019, Sinéad Gleeson’s gripping essay collection delves into considerations of selfhood through studies of the body and in particular women’s bodies in a wider cultural context, illuminating the author’s own extraordinary experiences, resilience, and insights into illness, art, representation, the medical system, and family, culminating in an extremely moving section addressed to her daughter. A brilliant, essential, necessary, and powerful collection.

Leonard and Hungry Paulby Rónán Hession.

My favourite novel of 2019, this extraordinary, peculiar, gentle, moving, touching, and incredibly funny debut had me gripped and laughing from the first line, and by the end sitting and thinking quietly in reflective rumination of all that I’d just read. It is a book I will revisit and reread again and again. Wonderful.

Arnold Thomas Fanning is the author of Mind on Fire: A Memoir of Madness and Recovery, Shortlisted for the Wellcome Bookprize 2019.

Susanna Crossman

Trying to choose my favorite 2019 book, I wonder how to pick from dozens of volumes read this year: the brilliant, burning pages of We that are young, a retelling of King Lear by Preti Taneja, Brian Dillon’s exquisite Essayism an experience like dancing on spider web strands, words by Anne Boyle, Buzatti, Derek Walcott, my discovery of Ann Quinn’s fiction which MUST be read, Anne Michaels lyrical novels whose humane, geological vibe, makes me want to weep, Conrad, Bachelard, Scott Fitzgerald, Carson, Perkins-Gilman, Jessica Sequeira, Mary Midgely’s philosophy, all of Woolf, Lucia Berlin’s casual, artful short stories, Evaristo’s stunning novel, scripted like a song, Maggie Nelson, Elena Lappin who made me laugh, Joris Luyendijk’s eye-opening finance book Swimming With Sharks, Francis Ponge’s paragraphs on sea shells…. The piles of books read in 2019 invade my house, books recommended by writers, suggested by friends. Like desire lines, one text leads to another, scores a path in the landscape of my reading, an outward turning, which in turn might turn me inside out. John D’Agata essay anthologies are stacked in tumbling, arcane towers, balanced by Jenny Offill’s The Dept Of Speculation, Canetti, Helen McCory and Cixous. Ali Smith and Nick Flynn tilt precariously by windows. Olga Tokarczuk’s Flightsis marked with yellow post-its on a shelf, next to Rilke, Kundera and Marina Warner’sManaging Monsters (recently re-read.) For twelve months, they’ve all inhabited me: Duras, Morrison, Foucault and Hass. For one year, their memories have become my own. How to single out one book? To choose the best book, I could use mnemonic criteria, selecting the text that, as Pigalia says, ‘persists in time like a scar,’ Pigalia believes the defining books of his life are not simply those he has read, but the books he can remember reading: the light, location, the angle of the volume between his hands. Rebecca Solnit writes, ‘A book is a heart that beats in the chest of another.’ In this way we meet a new vision inside each book, as Proust says, ‘receiving the communication of another thought while remaining alone.’

Me, I want all of my books from 2019. I surrender. They are my entire favourite.

Susanna Crossman won the LoveReading Short Story competition 2019.

Grahame Williams

My biggest discovery this year is the poetry of RS Thomas. I’ve been in awe of it since I was sent his Selected Poems back in the spring. A friend described him as ‘the BB King of poetry’, all sparing simplicity that makes you think you could do it yourself until you actually try and realise just how monumentally hard it is. However, as the RS Thomas poems have been around for a good long time I don’t think they technically qualify for a best of 2019 list. Instead, here are four (mostly) from this year:

Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky

In a way I’ve oriented all my reading this year by Deaf Republic, measured other books against it and the depth of feeling and excitement it evoked. I knew as soon as I flicked through the pages it would hook me. It’s a play, a folk story, a war story, lyric poetry with graphic elements to illustrate. The text on the page is devastating but if you can hear Ilya Kaminsky himself read it aloud then it becomes something even more, his voice is incantatory, unlike any other poet I’ve ever heard (you can hear him, for example, on episode eleven of the Faber Poetry podcast). Then I heard the BBC radio version and my obsession deepened even further.

Deaf Republic is also the clearest reflection of the multifarious nature my reading has taken this year – so much of it mediated by technology. I’ve tried to “read” wherever and however I can, in whatever tiny snatches of time are available.

Each weekday this year I’ve crossed London Bridge on my way to and from work and I’ve been trying to banish TS Eliot’s ‘so many / I had not thought death had undone so many’ from my mind. To that end, I try to listen to something that sticks two fingers up to The Waste Land as I cross. The most fervent and brilliant two fingers came from Jia Tolentino. I listened to her read Trick Mirror as I weaved in and out of the anti-terrorist bollards and men on executive scooters. The level of insight, intelligence and breadth of reference in these essays is astonishing, the writing lethal and addictive and the essays have lead my own reading in many brilliant and unexpected directions. Now I long to hear Jia Tolentino’s take on anything I might be interested in. I scan the contents page of each new New Yorker to see if she has a piece in it.

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff

This ought to be a life-changing book. However, ironically and shamefully, I read it on my phone, on Amazon’s app which no doubt tracked every twitch of my finger, every blink of my eye, along with the times and places I read (usually at lunchtime in a church on Bow Lane). My day job is in technology but I’ve never worked for ‘big tech’, although the lure has always been there. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism is genuinely terrifying, the central tenet that big tech is systematically robbing us of our right to the future tense (if you want to know how and why, you must read this book).

I go back frequently to passages I’ve highlighted to remind myself how gravely threatened and already compromised by Google, Amazon, Microsoft etc we are and what their motivations are for providing us with such indispensable functionality. I’ve been systematically trying to get Google out of my life ever since. Amazon I’m still sadly hooked on for how much it helps my reading life.

The Little Book of Garden Bird Songs by Andrea Pinnington and Caz Buckingham

My Mum bought this book for my little boy when she came to visit this summer. It has little round buttons down the right-hand side of the book with pictures of birds on them. When you press one of the buttons the book sings the song of the bird shown on the button. The pages within the book give you a description of the birds on the buttons. It is beautifully simple. It is pure joy. In the bath every evening my son and I sing the bird songs we’ve learned from this book.

Grahame Williams’ work has appeared in The Lonely Crowd, The Stinging Fly and the Letters Page.

Dai George

I’m afraid my book of 2019 – my trustiest companion; the book that has wormed into the crevices of my soul above all others – is a collection of short stories published four years ago which gathered up the lifetime’s work of a writer who died in 2004. A Manual for Cleaning Woman by Lucia Berlin has quickly become one of my totems. Berlin’s stories span the second half of the American century, but focus on people at the margins of that society’s consumerist pomp and circumstance: loners, drifters, survivors; the victims of alcoholism and heroin addiction; migrant workers and hospital support staff. As well as being graceful, gut-wrenching and endlessly humane, this is an influential document for anyone interested in the rise of contemporary American autofiction. Like her protagonists, Berlin suffered the ravages of alcoholism and lived among many of the collection’s psychogeographic flashpoints: laundromats, drunk tanks, Catholic schoolrooms; the heat, beauty and deprivation of the US-Mexico border (on both sides). Her writing demonstrates real, hard-won compassion: a surprisingly rare commodity in literature.

My favourite poetry book of the year was Isabel Galleymore’s Significant Other. I’m normally a little averse to writing that’s directly about animals per se, as opposed to ecology more widely, but Galleymore completely renovates a tradition that has been colonised by people like Ted Hughes. As with all good eco-poets, she understands that any attempt to capture nature is bound to fail – and, worse, is bound to impose on nature’s beautiful, valuable self-sufficiency – so her work starts from a fundamental premise of difference rather than familiarity. It comes scuttling sidelong out of the shadows, like one of the small, unsung sea creatures to whom she pays rapt attention.

A quick shout-out, too, to my top Welsh literary event of the year, Ed Thomas’s On Bear Ridge. We shouldn’t forget that plays are a type of text, and this was a particularly fascinating and poignant piece of writing. It has the absurd, claustrophobic texture of Pinter and Beckett but a kinship, also, with Brian Friel’s great play Translations, being equally concerned with the slippage and death of language. I have a feeling it will last beyond the charismatic performances of Rhys Ifans and Rakie Ayola, who brought it to life this year on stages in Cardiff and London.

Dai George is the author of The Claims Office.

K. S. Moore

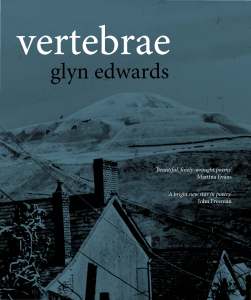

On reading Glyn Edwards’ Vertebrae I am struck by the intensity and vitality of language, how landscapes green into being, how words are like lines of the body. ‘A Frontal Lobe Love Poem’ is all at once, a conversation and an education, a flicker of electricity.

And ‘Wuthering Heights’ is so visually charged; to read it is almost to experience it: the ‘beetle brown earth’ and ‘unclouded sky at the Heights . . . as blue as your chilled fingers.’ Most of all, the portrait of a woman is brought to vibrant life.

By contrast, ‘The Birthday Walk’ reflects on the absence of Dylan Thomas, but also manages to imbue each line with phrasing inspired by his work: ‘Jackdaws grieving in the hollow castle, / Crows oiling rusted wings . . .’

I love the way Glyn has used his own unique brand of bird imagery: ‘chest glowing like a robin’s scarf, / So I undress half, fold the wings of a wintry coat / Over my hooked arm….’ While the form exactly mirrors that of Dylan Thomas’s ‘Poem in October’, there is never any doubt that this is a Glyn Edwards poem.

And I mustn’t forget the unforgettable ‘Night Fishing’, a brooding contemplation on the sometimes torturous nature of writing. I am haunted by the ‘barnacle dark’ and features of the pike that mark it out as having a glittering, yet dangerous appeal: its ‘greengold gills’ and ‘jewelled flanks’.

Anne Casey’s out of emptied cups is an explosion of word power. The idea of the body as a cup, is carried throughout the collection and begins with the opening poem, ‘out of a thousand cups’. The voice wonders what might have happened if another cup or ‘tiny egg’ had been chosen to hold her essence – a fascinating thought.

The melodious ‘if i were to tell you’ feels like a life path, and for me, appears to be encircled by its own aura of sunlight: ‘when sunbeams stream over yellow underbelly / a honeyeater feasting between gilding leaves . . .’

Meanwhile, ‘Wildness’ places animal features on a human frame, suggesting that a body’s full potential might not be realised until it sheds to release the soul within: ‘ I will curl up / wrap myself in your shed skin . . . all that had held you back / your wildness denied’.

‘All Souls’ brings the collection to a dramatic conclusion, as an image of Anne’s lost mother is presented against the backdrop of ‘the Atlantic’s roar’. When the mothers and babies that endured the horror of Irish Mother and Baby Homes, also take their place in the tableau, a hopeful reference to ‘hearts’ and ‘heavens’ suggests an awaiting peace for those who have suffered.

Both of these collections have been my constant companions over the last few months, and I continue to dip into an eddy of expression, finding something new, every time.

K. S. Moore’s poems have appeared in The Lonely Crowd, The Stinging Fly, New Welsh Review and Southword.

Gary Budden

The first of my books of the year has to go to Broken Ghost by Niall Griffiths, a writer who I’ve been reading with extreme enthusiasm for the best part of twenty years now. This latest novel plants us in firm Griffiths’ territory – the gorgeous Welsh landscapes around Aberystwyth, and a focus on the underclass and destitute of British society, but with a new seething outrage about austerity Britain and the Brexit fiasco. Three partygoers in the aftermath of a rave see, simultaneously, an angelic female form looming in the mist – a trick of the light, a Brocken Spectre, or a chance for spiritual salvation?

Nina Allan’s The Dollmaker continued to cement her reputation as one of the finest writers of imaginative fiction with this unnerving fable of dwarfism, dolls and obscure short-story writers, all set in a recognisable England that’s been just slightly knocked off balance. Technically this is a move away from the speculative fiction of The Race and The Rift, but the novel is a brilliant addition to Allan’s wider body of work and rewards both devotees and newcomers.

Non-fiction highlight of the year was Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, was a grim highlight for me, taking a novelistic approach to The Troubles, using the unsolved case of Jean McConville’s (‘disappeared’ by the IRA in 1972) as the lynchpin with which to tell the wider story of the conflict.

On the same theme, David Keenan’s For the Good Times – the follow up to the brilliant This is Memorial Device – is a hyper-charged, hallucinogenic acid-trip account of The Troubles written in visionary prose. I don’t think there’s anyone else writing stuff like this right now and I admire the nerve in even trying, let alone pulling it off.

Adam Nevill’s The Reddeningis a smart, literary horror totally embedded in the Devon landscapes of its setting, violently gruesome at times. The novel has a mind-bending sense of deep time linking us to our ancestral past when we shared caves with giant hyenas and monsters in the dark were dangerously real; and made the coastal path in Devon seem a terrifying place for a day’s walking.

And special mention must go to Outline by Rachel Cusk. Not published this year of course, but on the advice of numerous people whose opinion I respect, I relented and read it. The premise filled with me dread: middle-class creative writing teacher goes to Athens to teach creative writing. But I read the book in two days, addicted, to its Greek chorus of narratives unloading themselves to the narrator about relationships, family, and failed marriages, in a way that is completely engrossing.

Gary Budden is the author of Hollow Shores.

Chris Hall

The most extensive (and intensive) reading I have undertaken this year is reacquainting myself with Marion Meade’s magnificent 1987 biography of Dorothy Parker What Fresh Hell Is This? Having referred to it often in the past, and frequently dipped into it with considerable satisfaction and reward, this has been the first time I have read it in sequence from beginning to end.

Though celebrated in the popular arena as the witty and waspish fulcrum of the erudite and bohemian Algonquin Round Table, with a racy reputation for a libidinous, addictive and hedonistic personal life, it is all too easy to overlook the sheer range and variety of Parker’s literary achievements. Quite apart from the copious journalistic articles and assignments, the perceptive and literate critical commentaries, the stories, plays and film scripts, she was, to my mind, the most devastating poet of mental disorder and chronic depression that I know of, being able to capture not only the intensity of intolerable emotional anguish, but also that cold, seemingly ultra-rational fatalism that accompanies the contemplation and consideration of the efficacy and desirability, or otherwise, of suicide.

What makes the book mandatory reading, however, is the detailed and profound attention given by the biographer to the courageous and determined commitment to her Left-wing political leanings, stances and activities, galvanised during the Spanish Civil War, and reaching nemesis in the early Cold War and the era of MacArthyism, especially during her harassment by, and appearances before, the House Un-American Activities Committee. In revealing the full force of the writer’s utter contempt towards these shameless and shameful individuals, and her unswerving solidarity and friendships with other ‘unfriendly witnesses’, in particular fellow writer Lillian Hellman, Meade demonstrates that, far from being the insubstantial gadfly many commentators have asserted her to be, Dorothy Parker was one of the most articulate, principled and truly heroic figures that American literature has produced.

Chris Hall is the author of no fish.

Polly Atkin

2019 has felt like a very long year in many ways. Thank goodness for books.

A nonfictional account might have it begin with Ella Risbridger’s memoir/cookbook Midnight Chicken, roll down a hill with Elizabeth-Jane Burnett’s The Grassling, take a derive through Luke Turner’s Out of the Woods to find itself exposed by thawing permafrost in Kathleen Jamie’s Surfacing. I also recommend Emma Darwin’s This is Not a Book about Charles Darwin – not only for being one of the select few to talk about Tom Wedgewood, one of my Romantic era favourites – but for its painfully comic transparency about the writing process and writing business. I’m finishing my nonfiction year with Jessica J. Lee’s Two Trees Make a Forest, a beautiful follow up to her swimming memoir Turning.

I found company in the kingdom of the sick in Sinead Gleeson’s Constellations, Emilie Pine’s Notes to Self, Esme Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias and Jenn Ashworth’s Notes Made While Falling, which all give visceral accounts of bodily and metaphysical pain that had me exclaiming ‘yes, that’s how it is’ whilst reading.

My fictional journey took me to stranger shores yet, from the cultish claustrophobic edge-lands of Sophie Mackintosh’s The Water Cure, the postcolonical gothic of Sara Collins The Confessions of Frannie Langton, the contemporary tragi-comedy of Candice Carty-Williams’ Queenie, haunted and haunting houses in Amanda Mason’s The Wayward Girls, literally out of this world with Temi Oh’s Do You Dream of Terra-Two? with its mix of interpersonal drama, bildungsroman, space opera and clifi, and to different flavours of apocalyptic future in Katie Hale’s My Name is Monster and R.C. Sherriff’s The Hopkins Manuscript. This might seem like a bizarre mixture but maybe if I loved all of these books you might too.

Through middlegrade fiction I was carried off to the mountains in Sophie Anderson’s The Girl Who Speaks Bear and deep under the ocean in Frances Hardinge’s Deeplight, with both had refreshingly positive representation of non-normative embodiment, avoiding the narrative trap of magical cure in favour of learning to live with difference, differently.

If I have to pick poetry favourites, which is always hardest, they have to include:

Aria Aber Hard Damage

Vahni Capildeo Skin Can Hold

Chen Chen When I gro up I want to be a list of further possibilities

John McCullough Reckless Paper Birds

Lieke Marsman (trans. by Sophie Collins) The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes

Deryn Rhys Jones Erato

Emily Skaja Brute

Claire Trevien Brain Fugue

Arielle Twist Disintegrate/Dissociate

Belinda Zhawi Small Inheritances

and Ada Limon’s latest two collections Bright Dead Things and The Carrying which were published simultaneously in the UK in February.

My to-be-read pile is as vast and toppling as ever, and there are a lot of books I’ve haven’t included here because I haven’t finished or even really begun them yet, but it’s a start, right? There’s always next year … and the next … and the next …

Polly Atkin is the author of Basic Nest Architecture.

Cath Barton

I’ve very much enjoyed some of this year’s Big books: Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyportdemonstrates how the full stop might actually be getting in the way of the energy of many a story, Ali Smith’s Spring examines frankly the awfulness of our times and conjures heart-rending tenderness in spite of it, while Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other celebrates Black British women with a vitality and rhythm that is all her own.

But the book which stands out for me in what I’ve read in 2019, over and above these giants of the literary world, is Adèle by the French-Moroccan author Leïla Slimani, the 2019 English translation of her first novel, originally published in French in 2014 as Dans le jardin de l’ogre. I devoured this one afternoon back in March and it locked onto something in me. As an exploration of a woman’s search for meaning in her life this is – in my opinion – peerless. If once or twice Sam Taylor’s translation juddered, for the most part it was crystalline. Do not think this novel is about a sex addiction; it is about a quest for authentic feeling. Adèle is a 21st century Emma Bovary, and Leïla Slimani’s book deserves to be read as widely and remembered as long as Gustave Flaubert’s.

Cath Barton is the author of The Plankton Collector.

See Parts One, Two and Three of our Books of the Year feature.

Photograph by Jo Mazelis.