Books of the Year 2018 / Part Two

Contributors to The Lonely Crowd pick their favourite books of the year.

Gerald Dawe

With the volume of book publication hitting dizzying heights, matched by the promotional buzz of the market-place and sales via self-promotion, it sometimes feels that ‘literature’ has become just another product in the digital world of global media. Whatever is good for sales is itself ‘good’ and you can call that whatever you like. The market rules. The books of 2018 which caught my eye include Aidan Mathews’s impressively shaped and rigorous poetry collection Strictly No Poetry, published by Lilliput Press. Lilliput also published Thomas Kilroy’s ‘memory book’, Over the Backyard Wall, an intimate reimagining of the playwright’s upbringing in Kilkenny and his life as a student and young writer in the Dublin of the 1950s and 60s as well as his travels in the US where he met, along with many other famed writers, Flannery O’Connor. Derek Mahon’s Against the Clock had all the hallmarks of Yeatsian amplitude and reinvigoration; a stylish vision of the world around the Cork-based poet’s 21st century life. Further along the western seaboard in Mayo, Michele O’Sullivan’s This One High Field, has an austere equipoise and clarity that is becoming increasingly rare. Wendy Erskine’s Sweet Home had me utterly beguiled by the speed of ironic points her pitch-perfect stories convey. One book which awaits full immersion is Mary Gabriel’s substantial Ninth Street Women about five American women painters ‘and the movement that changed modern art.’ While I await delivery of Rob Doyle’s anthology, The Other Irish Tradition I have fallen under the spell of Lucia Berlin’s short fiction and memoirs including Evening in Paradise: a life bravely lived latterly in the face of health problems but, supported by family and friends, produced writing of the first order; something that old wizard Saul Bellow spotted early on. Bellow’s own follies are charted, alongside his unmistakable literary style, in the second volume of The Life of Saul Bellow, Zachary Leader’s unrelenting biography of the American master.

Christmas reading all in one go. Perfect.

Belfast-born poet Gerald Dawe’s most recent publication is The Wrong Country: Essays on Modern Irish Writing (Irish Academic Press.

Kate Hamer

The Necessary Marriage by Elisa Lodato.

I read this in the days where autumn palpably turns into winter, the weather sharpens and begins to bite and falling into a great book becomes an even greater pleasure. One of my absolute standouts from 2018 is Elida Lodato’s second novel The Necessary Marriage. Marriage is such vivid territory for the novelist and it’s perhaps surprising that it isn’t as richly realised as it is in this novel. Two marriages are at stake in the narrative, Jane falls in love with her older teacher when she is just sixteen and quickly finds herself married with two children and wondering at the choices she’s made. When Marion and Andrew move next door their intense and fiery relationship soon begins to spill into Jane’s life. This is a book that takes its time, it delves, layer on layer, until the inner workings of each marriage are laid bare – with all their individual passions and frustrations. Soon the two couples’ lives begin to cross over and an eerie sense of impending doom becomes a jarring, and ever louder, note in the background. Beautifully written, gripping and with atmosphere you can cut with a knife this will no doubt be one of my rare re-reads. Without giving any spoilers too there is also an ending that I definitely didn’t see coming!

Kate Hamer is the author of two novels, The Girl in the Red Coat and The Doll Funeral. Her new novel Crushed is due to be published in May 2019.

David Hayden

It’s been another extraordinary year for poetry with striking and original collections that I’ll be returning to far into the future: Sophie Collins’ Who Is Mary Sue?,Vahni Capildeo’s Venus As A Bear, Ishion Hutchinson’s House of Lords and Commons, Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead, Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas, Jenny Xie’s Eye Level, Shivanee Ramlochan’s Everyone Knows I Am A Haunting, Martina Evans’ Now We Can Talk Openly About Men. The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, edited by Jeremy Noel-Tod, recently out and long-awaited, is an instantly essential anthology. The Collected Poems of Frank Bidart is a very wonderful thing to have in the world.

There have been many fine books of short stories published this year but I’d recommend Prabda Yoon’s Bangkok set collection Moving Parts, translated by Mui Poopoksakul, two excellent debuts, A Lucky Man by Jamel Brinkley and Chris Power’s Mothers, Wolfgang Hilbig’s powerful and unsettling The Sleep of the Righteous, translated by Isabel Fargo Cole and Christine Schutt’s dark and diamond brilliant Pure Hollywood. Wendy Erskine’s Sweet Home is as good as anything I’ve read in years, witty, acutely observant and humane.

David Hayden is the author of Darker with the Lights On.

Susmita Bhattacharya

I didn’t manage to read as much as I would have liked to this year. This was due to various work commitments, school transitions (yes, kid moving from primary to secondary affected my mental space, so instead of reading, I was keeping on top of all the school emails and activities – in a good way!) But there were a few books that kept me going.

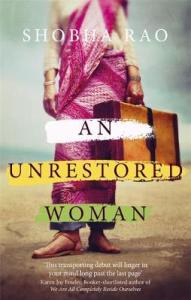

The first one was the short story collection – The Unrestored Woman by Shobha Rao. These linked stories were based around the time of the Partition, from the points of view of fearless or fearful women. These stories did not romanticise women’s situations but were blunt and matter-of-fact, which I enjoyed very much.

I took Claire Fuller’s Bitter Orange with me on a journey to Plymouth. On the way in, I could barely read a few pages. Cancelled trains, stormy weather and a taxi ride from Exeter to Plymouth shared with two prison wardens did not present me with the opportunity to read. But on the way back, once again cancelled trains and long waits at various stations had me completely hooked. In fact, on the last leg home I almost willed the train to slow down so that I could finish the book before I reached home. I got totally absorbed in the lives of the three main characters, and the climax at the end was not what I was expecting. All the train misadventures were totally worth it in the end – reader, I finished the book before my stop at Winchester. And then couldn’t stop thinking about it.

Catherine McNamara’s The Cartography of Others is another great read. I was particularly drawn towards short story collections this year, given the time constraints. And I found dipping into a collection time and again exciting and refreshing. I loved Cartography – the quietness of these stories, and the sensuality, how sexuality is explored is something I can only admire. I read this collection with a writer’s hat on as well. How to write a damn good short story. How to write good sex. And how to set these stories in such a variety of locations.

And the last one was the disturbingly good, When I Hit You: Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife by Meena Kandasamy. Such brutal writing. I ached for the character and found myself crying for her plight. I won’t say any more. One needs to read it to experience it.

I have bought more books this year that I have managed to read. So here’s to 2019 – with some more dedicated time to read and a teetering TBR pile. Very much looking forward to it.

Susmita Bhattacharya is the author of Table Manners and The Normal State of Mind.

Richard Gwyn

Sarah Manguso is a writer I have been pressing on anyone who will listen since discovering her in the summer. The writing defies easy categorisation, and is marked by a graceful minimalism. Her latest book is Ongoingness, a reflection on the past, and the diary that she no longer feels the need to maintain with the same obsessive zeal with which she began it as a teenager (and sustained for twenty-five years). With wit and admirable brevity, she succeeds in saying more in a few pages than many writers manage in a lifetime. She writes, she says ‘because it provides an escape hatch for the internal mess.’

One of the many fascinating reflections to emerge from Manguso’s book is that quality of forgetfulness that allows us to continue in the rut of accustomed thought, even when our circumstances have changed. One may even be inclined, on occasion, to forget as momentous a change as having had a baby. She writes:

‘Since the baby was born I still occasionally wonder whether I should have a baby, whether I should get married, whether I should move to this or that city I’ve already moved to, already left. All the large questions still float about me, and in its sleep-deprived dampened awareness of the present moment, my memory treats these past moments as if they’re all still happening.’

How that resonates! How often the momentous events of one’s life seem to be happening to someone else, to a distinct other or avatar, while our more familiar self goes about its business, oblivious. Not only births, but deaths, can be dissolved in everyday forgetfulness. There are times, for example, when I think to myself that I must phone my father, to tell him about something that has just happened, some small detail that will interest him – only to remember that he is no longer with us, that he died three and a half years ago.

Manguso’s sentences are like bright shafts of light: ‘I’ve never understood so clearly that linear time is a summary of actual time, of All Time, of the forever that has always been happening.’ And on the following page, this – which has happened to me also: ‘In class my students repeated what they claimed I’d said during the previous class, and, not remembering the words as my own, I found myself approving of them vaguely.’

In the ‘Afterword’ to Ongoingness, Sarah Manguso considers whether or not she should have included excerpts from her quarter century of diaries in the text of the book.She decided against it, she writes, because ‘the only way to represent the diary in this book would be either to include the entire thing untouched – which would have required an additional eight thousand pages – or to include none of it. . . The only way I could include my diary in this book then, was to refer to it and then continue on.’

Richard Gwyn is the author of several books including Stowaway and The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America. His latest novel The Blue Tent will be published in 2019.

Anne Griffin

2018 has been a year for reading some masters. These are three award-winning authors who not only want to make me write more but help me understand how to do it better.

I start with Richard Russo’s collection of stories, Trajectory. Published in 2016, this has slipped under my radar until now. Each story explores the secrets we carry around with us, too ashamed or afraid to share with those we love. We meet an auctioneer who is seriously ill, a professor struggling in her marriage, a semi-retired academic suspended from his job through an ill-advised desire to help a student with Asperger’s, and a writer whose wife has just been diagnosed with cancer. Russo is brilliant at showing how humans tick in all our flaws and kindness and courage. He is also exceptional at dialogue. The wittiest writer I know, read any of his work to find out how good you have to be to be a Pulitzer Prize winner.

I’m cheating with this next one. I haven’t actually read Jonathan Coe’s Middle England but have listened to it on Radio 4. In 1995 Coe was billed as one of the UK’s greatest satirists when What a Carve Up was published. Middle England proves this point once again bringing Malcolm Trotter, Coe’s likeable hero from earlier novels, back centre-stage with his on-going difficulties and eventual success in getting published. Starting in 2010 and bringing us right up to present day, Coe introduces us to a myriad of related characters, some loveable some detestable. Its central topic is Brexit. This novel doesn’t come down hard on either side of this debate but shows how the UK came to its fate in all its complexities. This is a clever, of-the-moment, book that is at times hilariously funny; a book that I cannot wait for my local bookshop to ring to say is finally back in stock.

My final pick is Anne Tyler’s Clock Dance. Really you just want to take Willa Drake, the main character, and treat her to something special. Willa is one of those women who has lived her life for other people, her two husbands, one who died tragically aged forty-one, the other who Willa married late, and her two sons, one in particular that you just want to throttle. When she gets a call to say her son’s ex-girlfriend has been shot and needs her help, it is no surprise that she drops everything to mind this woman she has never met, along with her nine-year-old daughter and their dog. But through this selfless act Willa somehow begins to listen to herself and finally makes a momentous decision about her life. Tyler’s writing is always touching. She makes you fall in love with her lead characters with the lightest of brush strokes. You are lulled by their quirky ordinariness, and their humanity. Anne Tyler is simply one of our greatest living novelists.

Anne Griffin’s debut novel When All Is Said will be published by Sceptre, 24th Jan 2019.

Caitriona Lally

I didn’t read as many new books as I’d have liked to in 2018. I came late to Robert Macfarlane and have been gorging myself on his beautifully described walks from previous years. I did read two fascinating books from the publisher And Other Stories – Alicia Kopf’s Brother in Ice, a wonderful hybrid novel dealing with the narrator’s brother’s autism and her obsession with polar exploration, and Amy Arnold’s Slip of a Fish, which gets us deep into the mind of an eccentric, troubled character who treats language as a toy to be pulled to its limits. I also loved Joanna Walsh’s Break.up, an intense impossible-to-categorise book about the end of an online relationship which was so original and gorgeously written I was sad to finish it.

Caitriona Lally won the 2018 Rooney Prize for Irish Literature for her novel Eggshells.

Glyn Edwards

Lucie McKnight Hardy

2018 was, for me, all about the short story. Writing them, yes, but also reading as many as I could get my hands on. Highlights of the single-author collections have been the hugely original How The Light Gets In by Clare Fisher (Influx Press) and Vesna Main’s powerful and compelling Temptation, A User’s Guide(Salt).

Anthologies have also provided me with a great deal of reading pleasure over the last year. Tales from the Shadow Booth Volume 2, edited by Dan Coxon, lived up to the high standard set by Volume 1, including as it did stories by some of my favourite writers of horror and weird fiction. High Spirits: A Round of Drinking Stories, edited by Karen Stevens and Jonathan Taylor (Valley Press) provided the perfect mix of humour and unease (and I’ll buy any book that features a story by Alison Moore). Another themed collection that didn’t disappoint was Seaside Specialedited by Jenn Ashworth (Bluemoose).

If I had to whittle down all the books I have read during 2018 to one single book of the year (which, after all, is the purpose of this exercise) it would have to be The New Uncanny, edited by Sarah Eyre and Ra Page. This might seem like a bit of a cheat, as this anthology was first published in 2008. It was, however, reissued this year, and I’m so glad that it was. A chance encounter with this book in my local (usually pretty poorly-stocked) library, six years ago while I was an OU student on a creative writing course, led to a fascination with the uncanny, and whetted my appetite for that which unsettles and disturbs. It made me want to write about the things I do. I recommend it to everyone.

Lucie McKnight Hardy has a limited edition chapbook forthcoming from Nightjar Press. Her debut novel, Water Shall Refuse Them, will be published by Dead Ink in July.

Angela Graham

Damian Smyth’s English Street explores, poem by poem and place by place, his home town of Downpatrick (reputed burial place of St. Patrick) and its hinterland. There is indeed an English Street, and an Irish and a Scotch Street in the town. It happens to be a part of Northern Ireland I know but not in the way this native does and he maps it by many means, breaking open (and into) archives, memories, yarns, official accounts, songs … and knitting these together in an unexhausted hunt for understanding.

There are demons in this collection, encountered in the everyday and there are mythical creatures and family history. We get the remembered experience of the poet and speculation about the lives of those he never met. But all this is here purposefully. The reader is in sure hands

An attractive and enriching feature of the collection is the set of notes provided, one for each poem. These offer a factual gloss or quotations, which operate like a kind of lens through which we can read the work. This is a flexible little mechanism which casts the light differently over the page and yields an interpretation which arises from the reader’s particular perspective on the material. I loved these, partly because they left me space to bring my own speculations to the party and encouraged a sense of mutuality in the exploration. This is not a poet declaiming his discoveries de haut en bas. Although he is both a confident witness and a robust engager with evidence that is often avowedly unreliable he knows his limitations; he knows the discomfort of being both native and ‘estranged’. This makes him all the more accessible and credible.

Included also is a list of every place mentioned in the book; more than 180 of them. This level of detail, married to a broad cultural context, creates a rich complexity. There is huge respect for the experience of the individual, for his or her suffering perspective, for the harrying by circumstance in whatever age. And this is also a book that made me, at times, laugh aloud. The poems’ titles offer a repeated invitation to note the juxtaposition of the portentous and the ‘down-home’, a disconcerting but illuminating experience that we’re all familiar with; for example, ‘The Lecale Metaphysics’, ‘The Killyleagh Utterances’ or ‘The Kilclief Pisarros’.

In ‘The Portofino Conclave’, the title jests with us in a slightly different way:

I was in an outhouse at the back of the Portofino

Making chips for the deep fryer…

But everywhere else it was the Age of Victoria –

A mouldered cottage off Irish Street someone was living in

When the Boer War broke out, the raw levies even now

In the caféitself in brown leather jackets: moustaches,

Tattoos; out-of-work teenagers, but hairy and grown-up,

Fingers cradling cigarettes with the burny bit inside,

Not moving their outstretched legs when I entered,

Skinny and ashamed, dragging a bucket behind me.

The conversational style is typical of the collection as a whole. It’s a hard style to achieve without descent into banality, especially over a long collection. Damian Smyth never puts a foot wrong. He exploits to the full its potential to float in, on its apparently unremarkable surface, shards of meaning and perception that stick fast. Thus, ‘The Portofino Conclave’puts before usa succession of violent men the area has known across more than a thousand years, passed through by the poet and his bucket of chipped potatoes:

as I made a way, small and afraid,

Then and now, still estranged, bringing the ordinary in.

We are all having to wonder how we negotiate a path through extreme and sanctioned violence and the men of violence have to figure out how to adjust to us.

A collection of depth and maturity, humour and compassion.

Angela Graham’s writing has appeared in The Lonely Crowd, The North, Poetry Wales, The Honest Ulsterman and elsewhere. She is the author of A City Burning, an as yet unpublished short story collection, edited by Gwen Davies.

Part One of our Books of the Year special can be found here. See the website this Saturday for Part Three.

© All contributors, 2018. Image © Jo Mazelis, 2018.