Books of the Year 2019 / Part Two

Contributors to The Lonely Crowd pick the best books that they have read this year.

Jo Mazelis

Around January of this year I began writing and researching a novel set in London in the 1970s. My research was varied, covering everything from music, history, politics and subculture. One of the key books, A Hero For High Times by Ian Marchant was recommended to me by a man I met on an eight hour train journey from Middlesbrough. The strange thing about this was that I hadn’t mentioned my research and the man didn’t look like the sort of person to be enthusiastically promoting a book which deals with (as the very long subtitle puts it) Beats, Hippies, Heads, Freaks, Punks, Ravers, New-Age Travellers and Dog-on-a-Rope Brew Crew Crusties of the British Isles, 1956-1994. The book aims to explain the cultural background to these subcultures and for Marchant the book is also an autobiography of sorts. Understanding why these subcultures emerged when they did and why they took their particular form is a very complex issue, but one important point Marchant makes is that books and reading were essential.

Perhaps this was why against my better judgement I found myself in 1976 struggling to read a book by Lobsang Rampa. That I also read The Family by Ed Sanders, nearly all of Richard Brautigan and a smattering of Herman Hesse and R.D. Laing, not to forget Jonathan Livingston Seagull and Valerie Solanas’ The Scum Manifesto, may illuminate this portrait of myself as a young woman in search of answers. Marchant provides a reading list in A Hero For High Times – I confess haven’t read all the books on it, but then such a list didn’t exist back then and if it had I would have rejected it as authoritarian.

Jenny Diski’s memoir The Sixties perfectly reflects the positives and negatives of the period and ends sadly with the author’s dumbstruck astonishment at how little had really changed by 2009. As Diski reflects on the fears of that generation, ‘I was quite sure that I would have to live part of my life … in a post-nuclear devastated world. If I lived at all.’ – this sadly echoes the mood in 2019 with climate change, deforestation and extinction constantly in the news.

Not Abba: The Real Story of the 1970s by Dave Haslam is a refreshing reminder that this period was not all satin flares, joss sticks, overlong guitar solos and concept albums, it was also Ian Curtis and Rock Against Racism and Bob Marley and The Slits and Ska. Haslam’s book is as much a social and political history of the UK as it is about the soundtrack to those years. It was men on picket lines in donkey jackets and David Bowie and the Yorkshire Ripper.

My research into the 1970s was interrupted by a need to dip further back in British history when I was commissioned to write something about Christine Keeler for the touring exhibition, Dear Christine. However Keeler’s autobiography Secrets and Lies did provide a vivid insight into the sort of rigid class-based society which the youth of ensuing years were seeking to change. Reading it I was struck by how mutable the figure of Keeler had been over the years. Depending on her interpreters’ judgement she was a slut or a victim, a glamour girl, a spy or the epitome of cool. In the years following the Second World War there was a terrible housing crisis in the UK meaning Keeler grew up living in a pair of converted railway carriages in Berkshire. It is easy to see how the lure of life as a model and dancer in Soho club would offer a young woman an escape from drudgery, abuse and poverty – but at what price ultimately?

Every so often I pick up my copy of Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of my Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures and skip-read it, which is to say, I read a chapter on Jimmy Savile, then another on the film Inception. Fisher’s essays might seem disconnected but illustrate the way each of us carry a particular lodestone of every book we’ve read, every song we’ve listened to, the films we’ve seen, the events we’ve experienced at first hand and those we know of from a distance. Fisher committed suicide in 2017 – earlier he wrote that ‘the pandemic of mental anguish that afflicts our time cannot be properly understood, or healed, if viewed as a private problem suffered by damaged individuals’ and he was right, yet it breaks my heart to say it.

I am still in search of answers.

Jo Mazelis’ most recent books are Ritual, 1969 and Significance.

Kathleen MacMahon

My stand-out book of the year was The Narrow Land, by Christine Dwyer Hickey. An unusual and immensely delicate novel, it’s set on Cape Cod in the summer of 1950. Michael is a child refugee from post-war Germany who has been settled with a working-class couple in New York, only to be packed off for the holidays to stay with a family of wealthy do-gooders on Cape Cod. The vulnerability and powerlessness of Michael’s situation puts him entirely at the mercy of his benefactors and throws in sharp relief the moral deficiencies that sully their best intentions. Michael finds an unlikely ally in the form of a middle-aged woman summering at a neighbouring house. She is the wife of the painter Edward Hopper and a fabulously complicated character, by turns bitter and brave. Like Hopper’s iconic portraits of American life, Dwyer Hickey’s painterly writing creates its own beautiful picture of the lonely battles that constitute the human condition. This immaculately written novel reverberates far beyond its mid-century setting.

Kathleen MacMahon is the author of This is How it Ends and The Long, Hot Summer.

Lucie McKnight Hardy

There are two books which stand out for me this year. Broken Ghost by (The Lonely Crowd contributor) Niall Grifiths is an exquisite depiction of how three people’s lives are irrevocably changed when they witness a vision on a Welsh hillside. Griffiths manages to craft a distinctive yet credible voice for each of these three characters, and each one is beguiling, if not likeable. Broken Ghost gives voices to the marginalised, and paints a disturbing yet moving picture of a community pushed to breaking point.

A psychopathic lighthouse keeper is the protagonist in my other book of the year. Geoffroy Lefayen has been assigned a six-month stint at the oldest lighthouse in France, where he pursues his passion for taxidermy, in Pharricide by Vincent de Swarte (translated by Nicholas Royle). Lefayen is a charismatic and deranged narrator and we watch, transfixed as he descends further into madness. This is an unsettling, grotesque and horrifying novel. It’s excellent.

Other books that have had me gripped, mesmerised and / or shocked this year have been In the Cut by Susanna Moore, a violent and explicit noirish thriller set in 1990’s New York which raises questions about sex, death and language; Sue Rainsford’s Follow Me to Ground, a dark and lyrical short novel which weaves folklore and horror together into a strange and unsettling tale; Mistletoe by Alison Littlewood is a finely-wrought ghost story which deals beautifully with grief and not belonging; and The Complex by Michael Walters, which is a brilliant, cinematic debut which sits somewhere between horror and sci-fi and captures the elusive nature of dreams and nightmares brilliantly.

Lucie McKnight Hardy is the author of Water Shall Refuse Them.

Jane Fraser

I declare my bias at the outset. I love Max Porter: the man and the writing. He is a super-intelligent, original-thinking and meditative person, as evidenced by all the enriching occasions when I’ve been privileged to listen to him talk about his world-view and writing, and see him perform his work (along with accordion, cello and audio) at the Hay Festival

Nowhere are these qualities more visible (and audible) than in Lanny, Porter’s second novel, which is perhaps even more innovative than his Dylan Thomas Prize winning debut novel, Grief is the Thing with Feathers. No wonder then that Lanny was longlisted for this year’s Booker Prize and film rights have been bought.

Though it’s sold as a novel, it reads as a long-form prose-poem, a superb soundscape illustrating Porter’s love of all forms and registers of language: the poetic and the everyday interweaving through the pages to create layers and textures and a cacophony of voices. It’s a hybrid of mythic folk-tale and domestic modern life exploring Porter’s musings on state-of-the nation ‘Englishness’ and his concerns for the environment. It’s set in an unnamed village within commuting distance of London, a village which as it says in the book blurb ‘belongs to the people who live in it and to those who lived in it hundreds of years ago. It belongs to England’s mysterious past and its confounding present.’

And it’s here that the characters play their parts: Dead Papa Toothwort, an ancient spirit who has seen all manner of life in this place; Mad Pete, a solitary artist who befriends the sensitive and idiosyncratic, Lanny; Lanny’s Mum, a writer; Lanny’s ‘distant’, city-working, Dad; and ancient Peggy, the village gossip.

Porter enabled me to see Lanny’s unique sense of wonder through this magical morality tale. In an age of intolerance, suspicion, and cynicism, it refreshingly turned my expectation of the unfolding narrative on its head, and tuned me in to a gentler, more innocent mental space, that is in real danger of slipping away.

Jane Fraser is the author of The South Westerlies.

Angela Graham

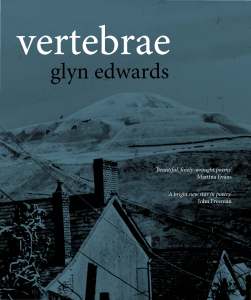

Vertebrae by Glyn Edwards.

This book does not disappoint. Some poetry collections do, in that they are uneven in calibre or have little substance. The thirty-three poems in this debut collection demonstrate two qualities (amongst others) which appeal greatly to me: they let me see the subject matter in an almost photographic way and they marry that descriptive brilliance with depth of perception. Here there is something worth seeing and something worth grasping.

One of the most striking poems is the second, ‘Night fishing’ which presents the poet’s dreams as pike in the depths.

At the spinning glint of a pen

Or the lure of a bedside light

A pike would flex in my neck

As ruthless as a fired shell

And rise at the tense skin of sleep

And break it like glass…

This poem passes Simon Armitage’s ‘Spelling Test’: Does the poem cast a kind of spell or charm? At the very least, does it create a world, even just a small but distinct world capable of sustaining human life, a world whose landscape we can inhabit for the duration of the poem.

Glyn Edwards moves with ease between prosaic or mundane circumstances and big questions such as mortality, human frailty or the challenges of parenthood. His perceptions are therefore well-grounded. He enjoys integrating material from television, remembered comments and snatches of conversation into new contexts and does this with a sure touch, creating a sense of wholeness, of a life being lived with awareness and readiness to engage. This is a stimulating example for the reader.

The book contains a transcript of a conversation between Glyn Edwards and the publisher, John Lavin. This is an enjoyable addition. I wouldn’t otherwise have noticed, for instance, that the number of poems matches the number of human vertebrae. Highly recommended.

And if I may sneak in two other recommendations – another debut collection, from the winner of the Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing, 2017. Glen Wilson’s An Experience On The Tongue . Assured and varied.

And this year I encountered the work of Jean Bleakney, scientist and poet. An experienced writer with an acute eye and ear.

Angela Graham’s A City Burning will be published next year by Seren Books.

Supriya Kaur Dhaliwal

2019 was the year of rereading Gillian Rose’s heart-rending memoir Love’s Work, and constantly quoting from it. By now, I’ve quoted so much from this book that I’m familiar with the NYRB edition that I own like one’s familiar with the territory of the house they grew up in, in which they could navigate from one room to the next without stumbling over anything even when they’re blindfolded. Love’s Work by Gillian Rose is a memoir which is intellectually and emotionally challenging in many manners. In it she writes about her ovarian cancer (the reason behind her early death at the age of 48 in the year 1995, in which I was born), reflects on postmodernism, Catholicism and Protestantism, divorce, eroticism, feminism, chemotherapy, immigration, atheism, dyslexia, half-lovers, half-friends. In the fifth essay in the book, Gillian introduces us to Father Dr Patrick Gorman, someone she was in love with—the affair was, however, quite torrid in nature. The essay opens with this paragraph which is one of my favourite opening paragraphs of all times because it’s laid with the kind of truth we often fail to articulate, “However satisfying writing is—that mix of discipline and miracle, which leaves you in control, even when what appears on the page has emerged from regions beyond your control—it is a very poor substitute indeed for the joy and agony of loving. Of there being someone who loves and desires you, and he glories in his love and desire, and you glory in his ever-strange being, which comes up against you, and disappears, again and again, surprising you with difficulties and with bounty. To lose this is the greatest loss, a loss for which there is no consolation. There can only be that twin passion—the passion of faith”. For me, Gillian Rose is a not only a philosopher with a jagged understanding of love and death, but a saint, and I look forward to rereading Love’s Work in 2020 and the years to come because even though its wisdom is immortal, it ages very well with you, like Gillian’s whiskey.

I also revisited many Iris Murdoch novels in 2019, and immensely enjoyed rereading Under the Net, Murdoch’s first published novel, from a fresher perspective. I first read it when I was 17 or 18 and have revisited it many times since then. Iris Murdoch in a letter to Raymond Queneau (to whom Under the Net is dedicated) on 7 August 1946, wrote, ‘I’m also very drawn to the Sartrean concept of anguish and to the portrait of man alone in the universe faced by choice, architect of his own values. What do you make of Sartre’s philosophy? [. . .]’ Murdoch attempts to combat Sartre’s social conditioning of humans by the medium of her character Jake Donoghue in Under the Net. In other words, in Murdoch’s eyes Jake is everything that Sartre’s Antoine Roquentin from La Nausée fails to be. Murdoch’s perceptions of the nineteenth century realism, and her understanding of the way how philosophical, political, aesthetic and narrative thought worked by the means of the medium of different techniques, draw a reader’s curiosity to fathom the understanding of her development of fictitious thought in her characters.

I enjoyed reading Tsering Wangmo Dhompa’s poetry collection In the Absent Everyday in which she extracts the best and worst truths from everyday habits and utterances. These poems are about belonging everywhere and nowhere, about home and exile. For me, these poems carry a whiff of home—the scent of Himalayas that’s ready to diffuse the air of other ‘homes’. My favourite lines are, ‘I know you by your walk / because we are from the same country. / If you were here to give safe passage—mosquitoes, / daddy-long legs, mollusks underwater—would / be left to do their job. West surrenders / to a new language. Bellwether / Billingsgate. Bivouac. Let us go / south. Let us go east. We come to be / courted. Our hands emptied’.

2019 was also a year of some excellent pamphlets, many of which were published by my favourite indie-presses. My favourites were:

1. ‘Ceremony’ by Caitlin Newby (Lifeboat Press)

2. ‘Curfuffle’ by Scott McKendry (Lifeboat Press)

3. ‘The Other Side of Nowhere’ by André Naffis-Sahely (Rough Trade Books)

4. ‘Milk Tooth’ by Martha Sprackland (Rough Trade Books)

5. ‘Six’ by Zaffar Kunial (Faber)

Supriya Kaur Dhaliwal is currently working on a sequence of poems about displacement, art and architecture.

Dan Tyte

I tend to think of books as timeless things, rather than reflective of a given twelve months, but of the books published since I saw that side of the sun, Lanny was the wonder which held both those opposing thoughts together and true. An elegiac study of the United Kingdom – or the English part at least – tied together with mystery and mysticism, made Max Porter’s book both as contemporary and antique as The Kinks around the village green or Blur in the park. Kevin Barry’s City of Bohane is always in my top three gift books (“like Peaky Blinders but on acid” I tell the recipient) and his Night Boat to Tangier was a buddy tragicomedy of bad decisions, lost love and, perhaps, some hope, somewhere between the small talk. Books published in previous solar journeys, but new to me, that rocked my world this year included Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry, ostensibly about a younger woman and a much older man (a writer, of course), which uses Desert Island Discs as a literary device I pinched my arm for not thinking of first, and Colum McCann’s Let The Great World Spin, a New York novel of the gutter and the stars that’s earned a place next to Barry’s Bohane on that gift list.

Dan Tyte’s most recent novels are The Offline Project and Half Plus Seven.

Aidan O’Donoghue

As as an inveterate Luddite, and sometimes misanthrope, Mark Boyle’s The Way Home: Tales from a Life without Technology particularly resonated. Still in his thirties – frightfully young for a recluse – Boyle doesn’t do things in half measures. Writing from his self-built cabin on a smallholding in Co Galway, his raison-detre is to go from ‘trying to save the world to savouring it.’ Far from pontificating and virtue-signalling, the book is a gentle treatise on living simply and opening our eyes to the world around us – all without once mentioning mindfulness.

Though 1978 is technically not 2019, I hope the editor doesn’t mind a minor indulgence in mentioning a book I paid so much money for that my kids weren’t fed for a week. It is Richard Brautigan’s June 30th, June 30th, his last ever published book of poems, and sadly, the last Brautigan in my collection. In their inimitable, offbeat way, the poems chart a 1976 trip to Japan and are laden with the classic Brautigan themes of loneliness, alienation, and naive wonder at a world in which he is an eternal onlooker. I have to thank a great champion of mine, Tom Morris, for first sending Richard Brautigan my way. Brautigan has brought immeasurable joy to my life, as well as crippling personal debt given that half of his books are out of print. Tom also has brought great joy to my life.

Aidan O’Donoghue’s work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review, The Stinging Fly, The Tangerine, The Moth and The Lonely Crowd amongst other places.

David Butler

I’d like to raise a seasonal glass to two daring debuts. The first is Last Ones Left Alive, by Sarah Davis-Goff. The novel’s protagonist, Orpen, follows in an impressive line of feisty female teenagers, from Katniss Everdeen of Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy through Ree Dolly in Daniel Woodrell’s chilling Winter’s Bone, Game of Thrones’ indomitable Arya Stark, and the eponymous heroine of Paul Lynch’s haunting Famine novel, Grace. Where the plot is highly filmic, leading to the inevitable battle between the undead ‘skrike’ and a race of female warrior ‘banshees’, the prose throughout is muscular and the imagery satisfyingly visceral. If poetry is concerned with making us see and hear afresh, then Eithne Lannon’s Earth Music excels. Her use of language is as precise as it is inventive: ‘currents below // carry on their secret life, ruffling / wavelets to a sandy paste, // lifting bubble-scruff to a frothy spin / of airborne river breath’, or again, ‘slow plishes drippling, mizzle and ink / stroking air. Finches shrill-singing, // swallows wing-flitting’. This is poetry to be read aloud, savoured on the tongue.

David Butler is the author of City of Dis and The Judas Kiss.

Jackie Gorman

Last Witnesses and Trouble in Mind

I’ve long admired the work of Svetlana Alexievich for her polyphonic writings, a genre she invented, a hybrid and hypnotic form which blends essays and oral history together. Her writings have traced the emotional impact of history in the Soviet and post Soviet people. Last Witnesses published in English for the first time in 2019, and translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, first appeared in 1985. It shares the memories of those who were children during the Second World War. The effect of these stories is poignant and cumulative. The day the war broke out many children remember that the weather was good, some were out playing with friends, and some were picking mushrooms in the forests with grandparents. Innocence is quickly lost and in its place comes fear and hunger, the most primal of human experiences. Parents are shot and houses are set on fire. The descriptions of entire villages razed to the ground and people eating grass and dirt are harrowing. There are childhood memories of seeing people frozen solid in the winter and hanging from trees. The descriptions are true with tiny detail as in all the great Russian novels, the bodies tinkled like wind chimes as they swung in the cold Soviet wind. Perhaps this sound is also a type of screen memory, where the mind makes another less unpleasant memory or association to protect us from the horror of what we saw or heard. It is an act of tremendous courage that Alexievich has brought these voices into the record of Soviet history, as they cannot now be silenced, these people who endured war and hunger. Her curation of these stories is deliberate and expert, we are left in no doubt that people are expendable for those in power and her craft is full of compassion and rigour. She is clearly a good listener. She has said ‘Flaubert called himself a human pen; I would say that I am a human ear. When I walk down the street and catch words, phrases, and exclamations, I always think – how many novels disappear without a trace!’

In March, 2018, I picked up a copy of the New Yorker and read a poem called ‘Giraffe’ by Lucie Brock-Broido and for weeks I couldn’t get it out of my head. ‘He was gentle and his heart was as long / As a human’s arm./ At night, the others of his species hummed to each other across/The woodlands there; no one knows how, exactly, to this day, / But you can hear their fluted sounds.’ The poem haunted me and I was sad to read that the poet had died on March 6th, just weeks before this poem was published in the New Yorker. I bought a copy of her collection Trouble in Mind and I fully began to appreciate what an amazing poetic voice had been lost, her shifting diction and syntax, her originality and her way of seeing the world. She said in an interview “a poem is troubled into its making. It’s not a thing that blooms; it’s a thing that wounds.” This collection drew me in completely in a way that was similar to the “Giraffe” poem, I couldn’t put it down. Reading the collection was an experience, it reminded me of reading the script in an old manuscript or old Irish or high German, something not fully understood at times and yet something catches the eye and draws you closer to appreciate the intricate craft and detail that is present and what you actually know. In that moment, you know that you understand. As in ‘Still Life with Feral Horse’ – ‘He will not/ Be handled by human/ Hands, not in this given life/ Of gratitude and tallow lamps/ and famous churlishness.’ It didn’t surprise me to read later she was considered to be an expert on the architecture of poems, teaching for many years at Princeton University, Harvard and Colombia. I only wish she was around a little longer to build and teach more poems with such an appreciation for the symmetry and magic held in and between the lines.

Jackie Gorman is the author of The Wounded Stork.

See our website next week for Part Three of our Books of the Year special.

Banner image by Jo Mazelis.